Crowd-sourced rainfall observations in Burundi

Last week, Aliane Nahimana successfully defended her MSc thesis about crowd-sourced rainfall observations in Burundi and the quality of Weather Impact’s weather forecast. For this work, she was supervised by TU Delft, Weather Impact and AUXFIN, and performed her work both in The Netherlands and Burundi. In her research, Aliane investigated the quality of crowd-sourced rainfall observations and its value for validation studies.

Mr. Bakoma Celeus from Kigabiro: “I use the AgriCoach weather forecast to plan my farming activities. I postponed the planting of my beans for 3 weeks until rain was forecast. The rain fell accordingly, so I am very happy with postponing the planting.”

Since 2018, Weather Impact is part of the G4AW Gap4All consortium that aims to support 100.000 farmers in Burundi with agricultural information services. A group of ca. 50 farming families receives one manual rainmeter and one tablet through the project. The tablet is used for financial transactions, reporting the rainfall observations and accessing the AgriCoach, the agricultural support app developed within Gap4All. The daily weather forecast and monthly seasonal forecast of Weather Impact are important pillars of the AgriCoach.

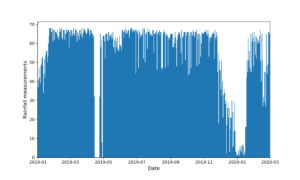

Officially calibrated ground weather stations are needed to evaluate the quality of these weather forecasts. However, in Burundi -and the majority of sub-Sahara Africa- trustworthy and continuous ground data is scarce. Therefore, Weather Impact and AUXFIN decided to set up a crowd-sourced rainfall observation network of 68 rainmeters in January 2019. In September 2020, this was expanded with 350 additional rainmeters. The percentage of farmers that reports daily rainfall measurements is very high, especially given the circumstances (e.g. priorities, theft, and internet connectivity). Over 2019, Weather Impact received 20.432 rainfall reports which is 81% of the expected reports (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Daily rainfall observations reported by farmers through the tablet from 1-Jan 2019 to 1-Mar 2020. Potential maximum is 68 measurements per day. Two periods had remarkably low reporting numbers: national internet black-out around 20 April 2019, and around the Christmas holidays.

Aliane’s analysis using neighbouring stations shows that 95% of the observations is trustworthy. Because of the local nature of tropical convective precipitation, all stations within a 13.5 km radius are considered “neighbours”, resulting in the number of neighbouring stations varying from 3 to 20. Two types of erroneous observations are flagged based on the minimum difference and ratio between the station and its neighbours: faulty zeros (e.g. a 0 mm station surrounded by >10 mm neighbours) and suspiciously high values (e.g. a 60 mm station surrounded by <10 mm neighbours).

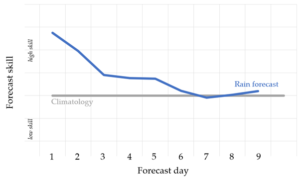

With these quality-controlled rainfall observations, the AgriCoach weather forecast is evaluated over the period January 2019 to February 2020. The quality or performance of a weather forecast is often described as the “skill” of the forecast. A forecast is considered skilful when it performs better (i.e. adds value) compared to a certain reference forecast, in most cases the climatology. Two characteristics of the AgriCoach weather forecast are evaluated: 1. the ability to forecast dry and wet days correctly, and 2. the accuracy to forecast the rainfall amount correctly.

For the reference forecast, daily rainfall observations of Gitega Airport from 1964-2008 are used, one of the region’s few long and continuous ground rainfall observations dataset. Using this history of daily rainfall observations, the chance and amount of rainfall that will fall on any given day of the year can be “forecasted”. For example, by looking at all 44 historical observations for March 10th from 1964-2008, it is “forecasted” that March 10th has a 30% chance to be a dry day with no rain and has a 12% chance to have heavy rainfall above 20 mm / day. By doing this for every day of the year, a so-called climatological forecast is constructed. Due to the distinct annual dry and wet season in Burundi, this climatological forecast is already quite skillful (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Forecast skill for different forecast days of the AgriCoach rainfall forecast (blue) and the climatological forecast (grey), based on the 1964-2008 climatology of Gitega Airport. The skill of a forecast describes the quality and usefulness of a weather forecast; the higher the skill, the more accurate the forecast.

The AgriCoach rainfall forecast skill score for first and second day (i.e. today and tomorrow) are high, and significantly higher than the climatological forecast. For days 3-5, the forecast skill scores flatten, but the forecast still clearly add value over to the climatological forecast. After day 5, the skill scores of the forecast and the climatology are very similar. This is in agreement with our expectations based on the nature of numerical weather models; their skill decreases with forecast time and for long forecast times (e.g. more than one week ahead) they often converge toward long-term climatology.

Next to the scientific research and forecast validation, Aliane also focussed on the logistics of the crowd-sourced rainmeter network. With the expanding network, what can be done to continue the success of the past two years, while at the same time ensure the quality of the observations? One suggestion that is already implemented is to automize a weekly monitoring service of the reported observations to quickly identify issues (e.g. internet connectivity). Also, a more extensive database on rainmeter metadata (e.g. location, photo’s, pole height) is needed to ensure standardized observations and therefore easier quality control.

Mr. Fabien Mariatunga from Kivoga: “With the rainmeter I can better understand the AgriCoach weather forecast. Every morning when I measure the rainmeter, I compare the amount to yesterday’s forecast.”

To conclude, Weather Impact would like to thank Aliane for her work, both the scientific research and field work in Burundi. And of course, this entire project and validation would not have been possible without the enthusiastic contribution of the Burundian farmers who report their valuable observations every morning.